"RAMT" Stats-, udenrigs- og forsvarsministre, der i nyere tid har sendt danske soldater i krig. Blyant på papir 19 x 29 cm. I alt 15 stk.

Simone Aaberg Kærn 2011-2013

OPEN SKY- AROS 2009 foto: AROS

Spider Sisters #1 2008

Smiling in a War Zone poster

Maleri afsløring Statsministeriet 3. December 2010

The Yellow Aeroplane Project - Gallery Martin Asbæk 2011

-

I'm currently working on:

The Yellow Aeroplane Project - Gallery Martin Asbæk 2011

Min Gule Flyver - en børne film; Kamoli Films og DR2

The Yellow Aeroplane Project

Ice Breaker

SciArt Expedition Swalbart June - August 2011.

the RAINBOW Project - Korea some time in the future.

Fighting For Living - dokumentar 8 Min, Udenrigsministeriet og UMANO - okt. 2010

Role of Women in Global Security, okt. Copenhagen 2010

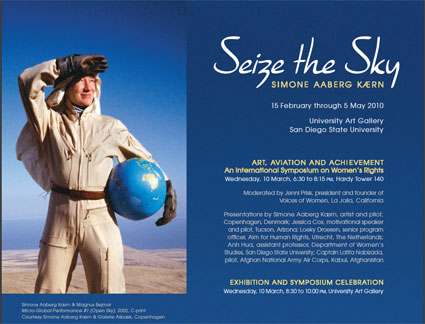

Seize the Sky - San Diego State University Art Gallery.

Lys over Lolland - August 09 - "Hvor jernbanen ender "

På lys over Lolland viste Simone Aaberg Kærn værket "hvor jernbanen ender.

Foto: Christian Lindgren

Simone landede igen på Lolland hvor hele hendes flyve eventyr startede. Det var her hun fik sin luftdåb, det var her hun første gang så et billeder af en kvindelig kampflyver fra den anden verdenskrig i en bog lånt på det lokale bibliotek.

Det var her hendes første flyver boede. Det er her hun første gang så den fine gule flyver som nu er hendes. Det var på hotellet i Rødbyhavn at hun lokkede manden i baghold som senere fulgte og filmede Smiling in a War Zone og som blev far til hendes barn. Rødbyhavn ved verdens ende og ved verdensbegyndelse er om drejningspunktet.I beskyttelsesrummet under den gamle godsterminal vises et lowkey flyve eventyr, en luftbro mellem fortid og nutid bestående af små fortællende videoer og erindrings foto fra det private arkiv. For første gang får vi indblik i historien bag Danmarks største kvindelige flyverhelt fortalt af den mand som backede hende i de første 10 år som kunstner og pilot. Igennem historien om pigen fra storbyen, der fik øje på himlen over Lollands langstrakte marker for at krydsede nogle af verdens højeste bjerge i et spinkelt fly for at virkelig gøre en drøm, finder vi en kærligheds historie om livet på Lolland og de indfødte, som hjalp hende med at få luft under vingerne.

Stilen er stille, konkret, kærligt og dokumentaristisk med små format billeder tekst og video fortælling.

Til åbningen af Lys over Lolland lander piloten i sin lille flyver der hvor jernbanen ender.Tak til: Gert Jørgensen, Jane Pørtner, Hove, SLV, Boje Hansen, Flemming Langben og mange, mange flere Lollikere.

6 x video med lyd indbygget i skabe, Lollandskort 120 x 300 cm MDF, 2 x 5 foto 21 x 30 cm

Compleated fortsat:

Udsmykning for det svenske flyvevåben.

"Farvel til industrisamfundet?" National Museet Brede, Maj 2009

Paint Space- Rundetårn Maj 2009

AROS - solo flight - ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum August 2008

NEW KATALOG : OPEN SKY -THUN

OPEN SKY - KUNSTMUSEM THUN 2008

* EMMY nomination for Smiling In a War Zone - New York Nov. 19th 2007

Simone Aaberg Kærn og Frederik Raddum- WE Love Asbæk , Copenhagen.

*2nd ANNUAL DANISH FILM FEST : LA

CELEBRATES 100 YEARS OF DANISH CINEMATippingPoint Germany 2007 – A dialogue between climate science and the arts”

* Symposium C6: The Artworld is Flat: Globalism – Crisis and Opportunity, Jay Pritzker Pavilion,

Chicago, USA.** 2007 Solo Show, Art Brussels, Martin Asbæk Projects,

SIMONE AABERG KÆRN - OPEN SKY AROS - Århus kunstmuseum

Vestgalleriet, 7. august - 5. oktober 2008

For første gang i Danmark vises Simone Aaberg Kærns succesfulde udstilling Open Sky på ARoS.

Simone Aaberg Kærn landede i Kabuls lufthavn i december måned 2002. Hun fløj selv dertil i sin 40 år gamle Piper Colt. Målet var at finde den 16-årige pige Farial, som drømte om at blive jagerpilot. Kunstneren, der tidligere har arbejdet med, hvordan kvinder blev kamppiloter under Anden Verdenskrig, så i pigen Farials ønske en parallel. Hun besluttede sig for at lære Farial at flyve og siden lade hende flyve selv henover Kabul.

Simone Aaberg Kærn har de seneste år høstet stor international opmærksomhed med sit udstillingsprojekt Open Sky, der har været vist i en form på Malmø Kunsthall og nu vises i en anden form på Kunstmuseum Thun i Schweiz. Dele af denne udstilling kan ses i museets Vestgalleri, der fokuserer på den yngre, eksperimenterende kunst.

________________________________________

OPEN SKY - KUNSTMUSEUM THUN

April 19 – June 15, 2008

Opening: Friday, April 18, 18:30 hrs

First solo exhibition of the Danish artist and pilot Simone Aaberg Kærn in SwitzerlandThe Kunstmuseum Thun presents a solo exhibition of the Danish artist and pilot Simone Aaberg Kærn, which is also the artist’s first solo exhibition in Switzerland. The works by Simone Aaberg revolve around women in flight. She confronts the viewer with the social, historical and political dimensions of aviation from various angles. Explosive topics, like the daily life of female fighter pilots in Turkey, or of female helicopter pilots in Afghanistan, also give leeway to poetic moments: A recurring theme in Aaberg’s work is human’s old dream of flying and the freedom high up in the air. With her keen eyes, the artist arouses the spectator’s curiosity for new approaches in flying and thus simultaneously works on gender-specific issues.NEW KATALOG : OPEN SKY -THUN

Go to KUNSTMUSEUM THUN press here!

AKTUELT:

KRIG, KUNST og DANMARK Holstebro Museum 23.marts til 30.Juni 2013

Udstilling kuratet af Elisabeth Porsing med

Simone Aaberg Kærn, Martin Nore, Henrik Saxgren, Claus Carstensen Niels Bonde

Peter Carlsen og Morten Schelde.

OPEN SKY af Simone Aaberg Kærn

(Afghanistan projektet, a micro global performance.)

på Teknisk Museum 12. april til september 2013

Installation view from Seize the Sky

Installation view from Seize the Sky

About the Exhibition

Simone Aaberg Kaern: Seize the Sky is a fourteen-year survey of the Danish artist's video works that address the sky as airspace unbounded by political borders and examine flight as a metaphor for individual freedom. Seize the Sky is Aaberg Kaern's premiere exhibition on the West Coast, and her first comprehensive solo exhibition in the United States. The exhibition and symposium are organized and curated by Tina Yapelli, director of the University Art Gallery at San Diego State University. The exhibition and symposium are sponsored by the San Diego State University Art Council; the School of Art, Design and Art History; the SDSU Center for the Visual and Performing Arts; the College of Professional Studies and Fine Arts; and the fund for Instructionally Related Activities. The exhibition and symposium are organized in conjunction with the fortieth anniversary of the Department of Women's Studies at San Diego State University. Simone Aaberg Kaern is represented by Galerie Asbaek, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Exhibition and Symposium in San Diego: http://artgallery.sdsu.edu/exhibitions/2010_kaern/

Pictures from exhibition and other events- press here

HEINRICH PRISEN 2009:

HEINRICH PRISEN klik her: Uro'erne får tildelt Heinrich Prisen 2009 . FOTO Nils Vest

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Udsmykning hos det svenske flyvevåben 2009. Air Combat udført i pulverlakeret alu. på lyseblå metal plader 6 x 30 meter.Kompas, taxi stribe og blå taxi lys. - se mere her

Foto Simone Aaberg Kærn

fra indvigningen, Team 60 performance, Foto: Swedish Air Force

Simone varmer kompas markeringer fra LKF på asfalten.

Fra arbejdet med udsmykningen på Statens Værksteder :

" work in progress " View into my studio Statens værksteder for kunst og kunsthåndværk May 2008

læs mere og se billeder i volmagazin klik her.

Trailer from "SMILING IN A WAR ZONE"

|

All you helping me with my projects thank you so much. No pilot fly alone.Thank you Copenhagen Airports (CPH) who store my artwork and airplane and have given me free take of and landings for life!